ASA Keynote Address 2021

Culture as King

Richard Browning (In partnership with Ann Mellow)

ASA Conference 12.08.21

Introduction

A former student from an Anglican school does something and makes national headlines. Does the school identify with this person and point to the values culture of the school?

It depends. Doesn’t it? It depends whether we can exert power over the ruling culture.

If you want to know whether a school has an impact on the values and character of the students in that school, best survey the students. This was Francis and Penny’s research. They questioned over 8000 students, from a mix of Anglican and non-religious schools, and they came to a bracing conclusion: “the collective world view of students attending Anglican schools generated an ethos consistent with a predominantly secular host culture”[1].

The scope of our challenge is vast. A student can put on a school uniform, wear a crest, and be engaged ‘at school’ for seven hours a day, five times a week for 9 weeks over four terms a year, but the cultural currents in which students are immersed run deeply into these hours while at the same time control whole bodied attention of the same students for hours many times longer.

This dominant, secular host culture is where:

the individual trumps[2],

the myth of scarcity prevails

freedom is an exercise of power,

competition dominates,

consumerism reigns,

simple and hierarchical dualities control our thinking,

truth is increasingly propositional and contestable,

ego and opinions weigh more than evidence and reason.

Going Deeper

So what does an ‘intentional culture’ look like in our schools and how is it distinct from our host culture?

There is much to be learnt from others. Have you ever searched: ‘list of Jewish Nobel laureates’ before? The bare fact is remarkable. While just over 900 prizes have been awarded since 1901, at a conservative count, over 20% of the laureates are Jewish. When less than 0.02% of the global population are Jewish, this is truly remarkable.

What lies at the roots of this astonishing phenomenon? I first encountered a piece of the answer in the writings of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. Judaism, like Christianity, is a faith rooted in memory but directed at the future. Education is an investment in the future. It is a practice participated in by families in the home – the more sitting in the company of scholars, the more wisdom – says Rabbi Hillel, pointing to the kitchen table as much as anywhere. He adds: “do not say ‘when I am free, I will study’, for perhaps you will not become free”[1].

Treasuring engagement in learning runs deep in Jewish culture. It is not just about Torah, and law, it is about life. When Jesus entered history, a whole range of honoured titles were placed on him. In Jesus’ Jewish context, the title of Teacher was up there as the highest among them.

So, what are the elements to an intentional culture shaped by our faith as Christians in the Anglican tradition, and how can they be effective?

[1] Pirkei Avot 2.6 https://www.sefaria.org/Pirkei_Avot.2?lang=bi

This Church

I start first by looking at the identity and purpose of the church. This is where Martyn Percy starts in his recent book, “The Humble Church”. He asks bluntly, what is the church here for?

Percy is not the first person to offer a simple, powerful translation for Logos as ‘verb’, but it gives you a sense of where he is coming from. Percy describes Jesus as the Verb of God, the action, the body, the drama of God in the world. That is, in the beginning is the Verb and the Verb was with God; the Verb was God.

Percy speaks of Anglicanism saying its original vision: is not a vision for a church – a set of rubrics for a denomination – it’s actually a vision for society out of which the church is a consequence.

He continues:

… the most important thing to begin with was that Anglicanism had a social vision for the kingdom and for practicing Christianity, a practical faith, being the verb of God in our communities, it is from that the church is a consequence[1].

The church in England did not create Anglicanism. Anglicanism and its vision came first and from this the church was created. This is crucial.

The chief work of the church is not church but participation in the project of God, to see and be and act in the world as God would and does.

This project has many names:

- It is called Jesus Christ.

- It is also called Shalom, or the Kingdom of Heaven;

- or being in the world as God is – we are to be God’s verb.

As Jesus taught, this is about ‘on earth as in heaven’.In a few paragraphs we have sketched out the identity and purpose of the Anglican church. As Jesus is God’s verb, so the church is the verb of God in the world. In the Anglican tradition this has five marks: telling and teaching the good news; tending to others’ needs; transforming what is crooked; and treasuring creation and all that is sacred[2].

[1] See the conversation hosted by Bishop Jeremy Grieves with Martyn Percy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ponk0tecZmg When asked specifically about Anglicanism and church as consequence not cause, Percy’s email answer was “Richard Hooker”.

On Jesus as Verb, see: “Humble Church, becoming the body of Christ”; Canterbury Press 2021.

Jesus is the “Verb of God”. Yes, the ‘Word became flesh’ (John 1); but as the Verb of God, Jesus ‘does’ God. Jesus is ‘the body language of God’, but more than that, is the actual expression of God – in words, deeds, actions, silences, walking, being – of what God is doing…

Because a verb is a word that describes actions or a state of being, we can learn to ‘read’ Jesus as he walks, talks, moves, speaks, is silent or angry; and yes, heals. Pp2-3 Percy.

[2] Here in the Diocese of Brisbane we bear two other marks: attuning to the holy, travelling in all things together: https://www.anglicanchurchsq.org.au/vision

Our Schools

If this describes the church

behind our schools, what can be said of the identity and purpose of Anglican

schools?

Dan Heischman was brought in a

few years ago to help push us as Australian Anglican schools deeper into this

examen. Some might see this as an exercise in folly, for we all know, one of

the hallmarks of Anglican identity is that we are able to shape our own

identity. However, unless this identity is framed within a shared or common

identity beyond the confines of our own campus, we are in danger of cementing

the dominant individualistic culture of the world in which all truths and

values are claimed to be equal.

There are some marks that are

common. Here in Southern Queensland, we launched last year a simple statement

built on earlier iterations. Our essential statement is neither radical nor

novel. It is as elegant as it is true[1]:

The vocation of Anglican Schools is

education

driven by a vision of humanity

shaped by the image of God

made visible in Jesus, present

in every human being.

- Like the church, we go about a work whose purposes lie in the future.

- Like the church, our work rises from a vision of the world at large and humanity’s place in it.

- Like the church, our work rises out of deeply set values bound to the character of God whose heart is turned outwards in love.

- Like the church, our work is about being present in the world as a gift.

- And just like the church, there are some marks that characterise our identity.

Here in Brisbane, we describe ourselves using six marks.

The first and most important is incarnational, a technical word I know.

Some things are real but cannot be seen until they are manifest in a body, in a time, for a place. This is Grannie. She is the epitome of patience; of humble generosity; quiet, unassuming, irrepressible love. These things lived in her. And even now that she is gone, I can clearly picture them in her.

Words like love, fairness, justice, wisdom, community, trust, kindness have no substance until somebody lives them, embodies them, makes them real within their own substance.

Jesus is God incarnate, the Verb of God, God from God, light from light, true God in time and place. So in schools, what is real but unseen must be made visible; our schools must be incarnational.

Each Anglican school should know what essential words come to life in their community. What words live in your school? By what words are you known? These words should be true and good and emanate from the heart of God whose love lies at the heart of the universe.

The five other marks of Anglican schools are all incarnational, they are true yet need to be made visible.

Our schools are intellectual, unapologetically so. We have minds that demand testing and stretching as much as truth needs pursuing and fearlessly living into.

But we are not brains on a stick. We also have hearts and souls within bodies that are woven in a fabric of interconnection. So, we are pastoral. We practice knowing our students and caring deeply for them.

Our schools are faithful. The story of the image of God and the face of love in the person of Jesus is held up and shared.

Our schools are missional. We have good news to tell and teach. But that mission must also be present in the world in a way that brings healing and justice: every member of our school has a responsibility to participate in a tending and treasuring and transforming for a good that is common and universal.

Our schools are hospitable. We bear the cost of hosting people of any and every kind, regardless of race, culture, gender, sexuality, religion, privilege or none.

You will remember I started with Rabbi Jonathan Sacks and where education sits within the heart of Jewish practice. Education is not first an instrument for new generations to be formed into ‘Jewishness’; education is at the heart of the nature of being Jewish.

Education lies at the heart of the health of a nation. Education lies at the heart of Anglican schools where the health of civil society lies at the heart of Anglicanism.

Anglicanism’s first imagination is engagement not institution; social vision not church. It should be apparent that our church has digressed. This deviation is exaggerated here on this continent when our church’s imagination accompanied empire with an agency closely knit to the activity of colonisation.

Our Purpose

Identity and purpose are bound where doing arises from our being. The question that best tests this unity in our schools is simple: what are we educating for?

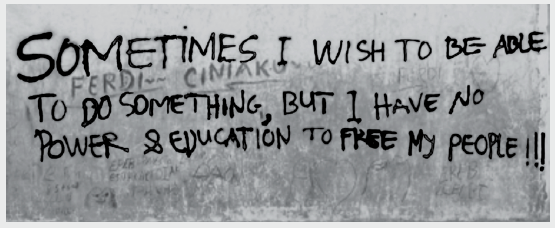

Kirsty Sword Gusmão, former First Lady of Timor-Leste, once shared this photo:

The photo was taken in May of 2002 in Dili. This date is important, as barely months later, in the same city, highly educated Australians bugged a room, won the upper hand in negotiations and diverted billions of dollars of oil and gas away from one of the hungriest nations on the planet[1].

Timor had emerged from an extremely violent twentieth century, a victim of multiple foreign occupations. This graffiti tag is not a generic “Viva Timor-Leste”. It is different:

“Sometimes I wish to be able to do something,

but I have no power and education to free my people”.

Notice the cry of poverty, the anguished lament of unmet longings whelmed by the absence of agency.

Notice the core value of community at the heart of the longing.

Notice the connection between education and power and the relationship between education and liberation.

Education liberates. Whilst an educator creates the space for learning to grow, the work of learning can never be done for the learner. The learner is always responsible for the power they come to possess. The first power learning gives is the dignity of agency and self-determination.

What are we educating for? Each school has to answer that question.

- If we are not educating for truth, dealing with things as they are and their inherent dignity;

- If we are not educating for deep knowing and a steadfast wisdom;

- If we are not educating for compassion through values framed by the God of the cross and a flourishing grounded in the flourishing of all;

- If we are not educating for community with a heart for justice;

- then what are we educating for?

The social vision at the heart of our identity demands this question be answered.

The church of England Education Office has a systemic response which is proving to be as compelling as it is effective. Their work is easily accessible and provides a matrix to help grow educational leadership and frame culture across every element of a school’s operation. This is a (slightly amended) summary[2]:

Educating for Dignity means

- Honouring the essence of things, the truth of things, treasuring what is precious,

- modelling respect, especially the inherent worth of each person

Educating for Wisdom means

- Engaging mind with heart, body and soul in practices of deep knowing

- nurturing the love of learning,

- cultivating hunger for wisdom and mastery in knowing how we come to know

Educating for Hope means

- awakening students to values and values systems,

- forming outward facing consciousness, with values biased towards loving kindness, choosing life and the common good

- enabling relationships of trust within vulnerability

Educating for Justice means

- building community, equipping hearts and character to work for each other’s flourishing, serving neighbour and the common good

- Enabling the capacity to be fully present to the other, a ‘being-for’ across a diversity of contexts

- Creating habits of generous hospitality, peace-making, kindness and mercy, justice and solidarity.

That’s what we are educating for.

Drawing down deeply on our Christian narrative and Anglican tradition will increase our schools’ capacity to do its essential business, which is to educate. It will simultaneously deepen the culture that honours the image we all bear – the image and likeness of God.

[1] See “Oil Under Troubled Water: Australia’s Timor Sea Intrigue” by Bernard Collaery

[2] https://www.churchofengland.org/about/education-and-schools The Church of England work is impressive. The C of E ‘Vision for Education’ paper was published in 2016. Learning of the foundational story of this is interesting. Andy Wolfe has been very generous with his time and welcomed long conversations and many questions. This vision for education does not ask ‘how are we different?’, it asks ‘how best do we educate’?; it asks how do we be deeply Christian and serve the common good?; it asks how does this work in practice? The subsequent publications are very practical, build on previous work and take the principles into teacher and leadership formation and practices for the classroom (see: Ethos Enhancing Outcomes; Leadership of Character Education; Called Connected Committed, 24 Leadership Practices for Educational Leaders). The summary offered here incorporates a matrix that is argued for in a separate paper ‘Educating for’, Richard Browning. It brings four philosophical domains to what they call an ‘ecology’: ontology, epistemology, hermeneutics, ethics. I argue these give an order and great richness to the original categories. Paper available on request.

Conclusion

I close with a final story about culture.

Sanjeev and James were friends working in an inner east Melbourne Start-Up. Sanjeev got married. It was a traditional, colourful, noisy, lengthy celebration. James cooed over Sanjeev as he relayed his exotic stories. Sanjeev bristled then rebuked James saying:

Wait. Stop. Are you talking to me here about how much you love me having and loving my culture because you don’t have one? You need to understand, whenever your ‘culture’ – which you think doesn’t exist – rubs up against mine or any other, your culture dominates; your culture wins.[1]

This is instructive. In Australia’s version of a western liberal democracy there is a dominant but ‘invisible’ culture. It rules our lives and the lives of our students. Unless an intentional culture is masterfully, purposely, faithfully, created students remain uncritically steeped in the dominant host culture;

as I mentioned in the beginning this is where

the individual, scarcity, power, competition, consumerism, dualities, ego

all roam triumphant, unleashed and unchecked.

The vision of humanity we receive from God’s Verb, Jesus, speaks into this culture, flips and transforms it:

person is realised through relating,

abundance is available, for all,

freedom is experienced through service

and power is expressed in giving, not possessing;

compassion is the rule,

dignity reigns,

if ever there is the ‘other’ they are our neighbour,

truth is relational and for living into

and ego trained in humility is a foundational value.

This vision, grounded in God’s verb inspires hope, fosters deep learning and transforms communities.

Anglican schools are about excellence in education,

shaped by the image of God whose purpose is

bringing forth light and liberation for the increase of all.

[1] I heard this story once on ‘Inverse Podcast’ with Jared McKenna but cannot for the life of me find which one.

No Comments Yet